Supported Parents, Thriving Kids

The Benefits of Social Supports for Latino Families with Young Children

Adriana Lopez’s daughter, Maria, came home from her second day of preschool in Rio Rico, Arizona, not with a finger painting or a craft project, but with a story to tell. One of the other kids, she said, had hit her.

Adriana, who had immigrated to the small town just 15 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border more than a decade earlier, says that had it not been for a parenting course at Rio Rico’s community center, she may not have known what to do about the incident.

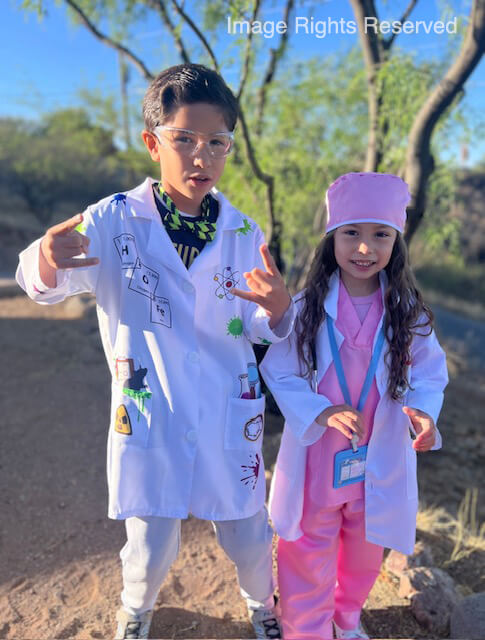

Raymundo Lopez, 9, and his sister, Maria Lopez, 6, show off their Halloween costumes. Their mother has worked to ensure they retain a connection with their Mexican heritage, language, and culture. Use restricted to the 2025 National Latino Family Report. No reproduction permitted.

“The teachers didn’t tell me about it,” Adriana remembers. “If I hadn’t taken the class, maybe I would have said, ‘Oh, well, these things happen,’ and because I wasn’t sure or because of fear or because I thought it was asking too much, I wouldn’t have spoken up. But instead, I sent an email to the director. I said, ‘You have to notify me if something happens with my daughter. It’s not right that you didn’t tell me.’”

“I took that class several times, and it opened my eyes. I learned what my rights are as a mom,” she says.

Early parenthood can be isolating and confusing even in the best of times, but for Latino immigrant parents like Adriana, language barriers, cultural differences, and physical distance from loved ones can make it even more challenging. Nonprofit and government programs aimed at supporting immigrant families — things like parenting classes, Home Visiting, early-intervention services, and affordable child care — can help parents succeed at a critical time in their kids’ development.

Supporting a Strong Start

Adriana enrolled in the parenting course before Maria was born. It was 2018, and her firstborn, Raymundo, was 2. The course utilized AP-OD’s trusted curriculum to support parents as leaders in their child’s early development. For Adriana, it felt like the world opened up. Not only did she connect with a whole village of fellow parents, but she also started to feel more confident as a mom.

“The first two years, I felt lost,” she says. “I was like, ‘He’s crying. What’s wrong?’ OK, I’ll take him to the doctor. After taking the class, I had a better idea of what to do and how to do it.”

Through AP-OD’s curriculum, Adriana and her fellow students learned that 90% of a child’s brain development occurs during the first five years of life, and that activities like reading and play help children learn and grow.

The Lopez family. Use restricted to the 2025 National Latino Family Report. No reproduction permitted.

Adriana and her husband, Ray, waited seven long years to become parents, and when Raymundo was born, Adriana knew she wanted to be the one to support his early development. “I longed so much to have children,” she says. “And when that moment came, I said, I don’t want to be at my job when he takes his first steps or says his first word. I want to be with him. I don’t want to miss those moments.”

High-quality child care and early learning centers are well-positioned to offer brain-boosting activities to children, but for many Latino parents, child care is cost-prohibitive or hard to access in their area. In the 2025 National Latino Family Report, nearly one in four surveyed parents said they had to reduce their work hours because they couldn’t find affordable care. Another 23% reported lack of child care kept them from working at all.

If Adriana had needed child care, availability may have been a barrier. In 2019, 37.3% of children in rural communities like Rio Rico lacked access to child care. There simply weren’t enough child care centers to meet families’ needs. The pandemic didn’t help. In the early months of 2020, the child care industry’s workforce shrank by 34% as child care centers closed their doors. That’s more than twice the average decrease across all industries. It took at least three years for numbers to rebound.

Adriana had the financial flexibility to stay at home, but most families don’t have that luxury. The average cost of child care for an infant in Arizona is $15,625 per year. That’s 16% of the median household income — or 30% more per year than the cost of in-state college tuition.

Latino families are less likely, on average, to send their children outside the home to receive child care. About 53% of survey respondents reported utilizing child care, compared to the national average of 59%. Of those whose children did not receive care, families cited affordability as a key reason. Lack of trust in non-familial caregivers also topped the list.

If she’d had family members close by, Adriana says she would have called upon them more often for help. The majority of Latino families who took our survey echoed the value of family support. As in years past, the vast majority of respondents (90%) reported preferring trusted family members to care for their children.

A Bright Future for Raymundo and Maria

Raymundo Lopez, 9, and his sister, Maria Lopez, 6, pause during a scooter ride. Like the vast majority of parents surveyed for the 2025 National Latino Family Report (88%), their mother Adriana wants them to be bilingual. Use restricted to the 2025 National Latino Family Report. No reproduction permitted.

Adriana’s days of bottles and diapers, first steps and sleepless nights are behind her. Today, Raymundo is an outgoing 9-year-old who loves Star Wars and excels in school. Six-year-old Maria plays basketball and takes ballet lessons. Both attend elementary school, and Adriana is thinking ahead. She’s working to become a substitute teacher at their school.

When he was little, Raymundo only spoke Spanish, but these days, English is his language of choice. He speaks English at school with his teachers and friends. But Adriana is working hard to help him learn more and more words in Spanish.

Like the vast majority of parents surveyed for the report (88%), Adriana wants her kids to be bilingual. It’s important to her that they maintain a connection to their culture and language.

As Raymundo’s teachers have pointed out, there are other benefits to bilingualism. Speaking more than one language can improve memory, boost creativity, and stave off mental decline in old age.

There are more than 5 million English learners in U.S. schools, 76% of whom speak Spanish. More than 9 out of 10 surveyed parents said it’s important for child care facilities to offer multilingual and multicultural education to help students retain a connection to their culture.

Adriana also knows that being bilingual will set her kids up for success. Studies have suggested that bilingual candidates are more likely to have a job and more likely to receive a higher salary than their monolingual peers.

“My goal is for them to be bilingual so they can get a better job, whatever they decide to do,” she says. “It is an advantage. That’s why I’m doing this for them.”

Like so many other Latino parents who prioritize bilingualism for their children, Adriana is doing more than teaching her kids a second language. She’s giving them the tools they need to walk confidently in two worlds — with pride in their roots and hope for the future.